June 12, 2019

Local juvenile duck-billed dinosaur fossil discovery reveals new details about its appearance

Researchers Eamon Drysdale, centre, François Therrien, right, and Darla Zelenitsky with fossil.

Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology

The discovery of juvenile specimens of the duck-billed dinosaur Prosaurolophus maximus greatly improves our understanding of the growth and life cycle of hadrosaurs, according to new research out of the University of Calgary’s Faculty of Science and the Royal Tyrrell Museum.

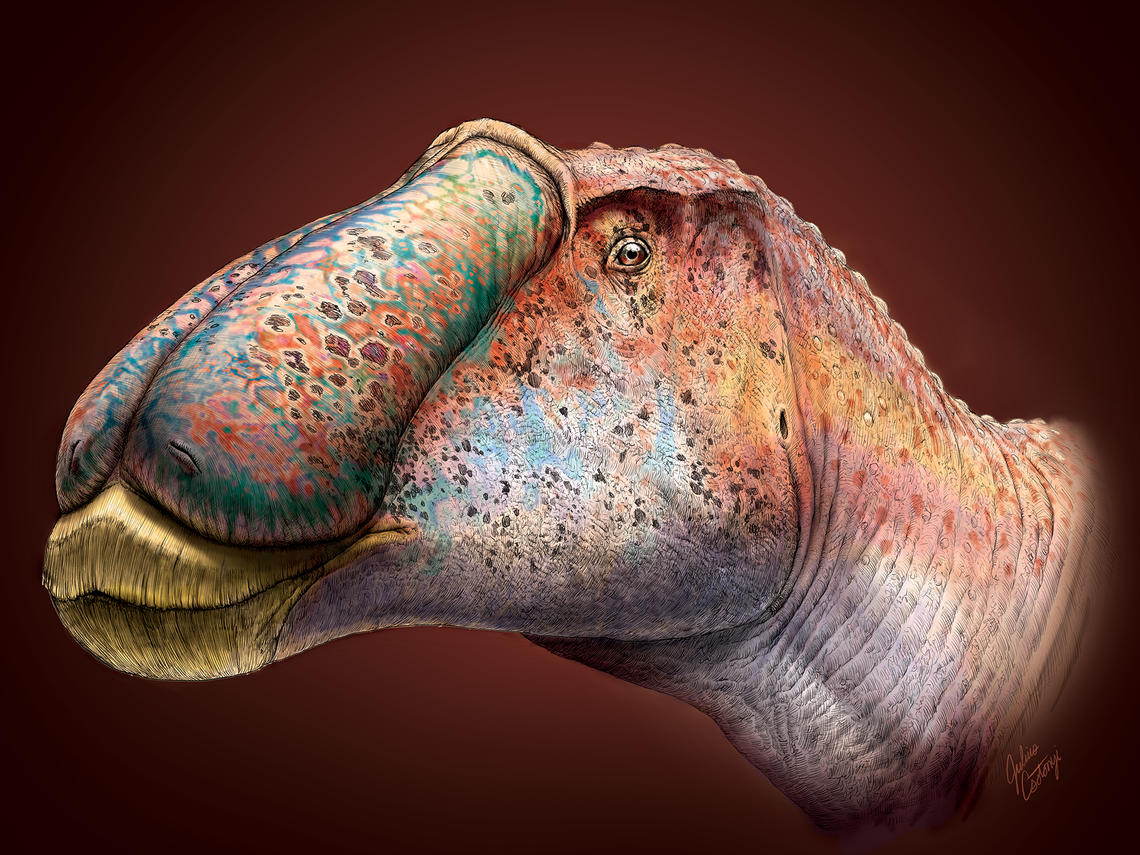

Showy snout and bony crest on forehead developed as Prosaurolophus matured

Prosaurolophus is a large, herbivorous duck-billed dinosaur that lived in southern Alberta and northern Montana around 75 million years ago. Unlike many duck-bills, which had a large bony crest on their head, Prosaurolophus had only a small crest on the forehead. These fossils are the youngest and smallest individuals known for the species, and researchers were interested in determining how the crest changed as the animal grew, as this feature has been thought to be related to sexual maturity and mate attraction.

“We noticed that the bony crest grew very slowly in Prosaurolophus and remained small, unlike what happened in some duck-bills, which rapidly developed a large bony crest,” says Eamon Drysdale, graduate student in the Department of Geoscience and the study’s lead author. “Instead, rapid changes in the snout as the animal matured suggest that a soft tissue structure may have associated with the nostrils and used for display. “

“In Prosaurolophus, the snout would have been the primary display feature rather than the large head crest of other duck-bills.” Drysdale adds.

Artist's illustration of the hadrosaur in the study.

Julius Csotonyi

Preserved fossils discovered in ancient inland sea

This idea of a showy, fleshy snout had been hypothesized previously by paleontologists, and the new study now offers evidence to support this premise.

“Gathering evidence to support this hypothesis was difficult because it required finding the fossils of juvenile individuals, which are very rare,” says Dr. Darla Zelenitsky, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Geoscience and Drysdale’s supervisor.

“It took over 30 years for the Royal Tyrrell Museum to recover a decent growth series for the species,” Zelenitsky tells. “Our students are now benefiting from the collection and preservation of these fossils by the museum.”

The unusual setting in which the fossils were discovered also shed light on the environments in which Prosaurolophus lived.

Dinosaurs were land dwellers, so their remains are usually found in rocks deposited in rivers and lakes. This was not the case for the three juvenile Prosaurolophus fossils featured in this study, which were found in muds deposited at the bottom of an inland sea that covered Alberta about 75 million years ago.

Front half of the skeleton of a juvenile Prosaurolophus dinosaur.

Eamon Drysdale, specimen at the Royal Tyrrell Museum

“It was very fortuitous that three young individuals of the same dinosaur species happened to float out to sea and sink to the bottom where they were buried,” says François Therrien, curator at the Royal Tyrrell Museum, who also supervised Drysdale. “Their preservation in the fine mud contributed to the fossilization of large patches of skin showing the flanks of these animals were covered in a mosaic of large and small scales.”

As for why and how these dinosaurs ended up at sea, Drysdale says “It may have been that these particular dinosaurs spent a lot of time in coastal areas. Living close to the coast, these animals may have been more easily washed out to sea after they died.”

The research group also included Dr. Dave Weishampel, PhD, from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and Dr. David Evans, PhD, from the Royal Ontario Museum. The study was published in the May issue of the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Drysdale graduated with an MSc at the June 6 convocation ceremony; he plans to continue his post-graduate education by pursuing a PhD in dinosaur paleontology and hopes to continue conducting research in Alberta.