Sept. 24, 2014

Inuit folklore kept alive story of missing Franklin expedition to north-west passage

On September 6, Canada’s prime minister, Stephen Harper, announced that one of the fabled lost ships of Sir John Franklin’s expedition had been found off Hat Island, south-west of King William Island.

The ships HMS Erebus and Terror, which sailed from England in the summer of 1845, were aiming to chart the north-west passage. They disappeared into what is now the Canadian Arctic. Stranded in the ice north-west of King William Island in the summer of 1846, the ships were abandoned by the surviving officers and men in the spring of 1848.

The sole meagre message which was found reporting their fate states that they started south, hauling boats on sledges, aiming for the mouth of the Great Fish (now Back) River. It is assumed that they planned to ascend the river in the hope of reaching the nearest Hudson’s Bay Company’s post, Fort Resolution on Great Slave Lake. Of the 129 men, not one survived.

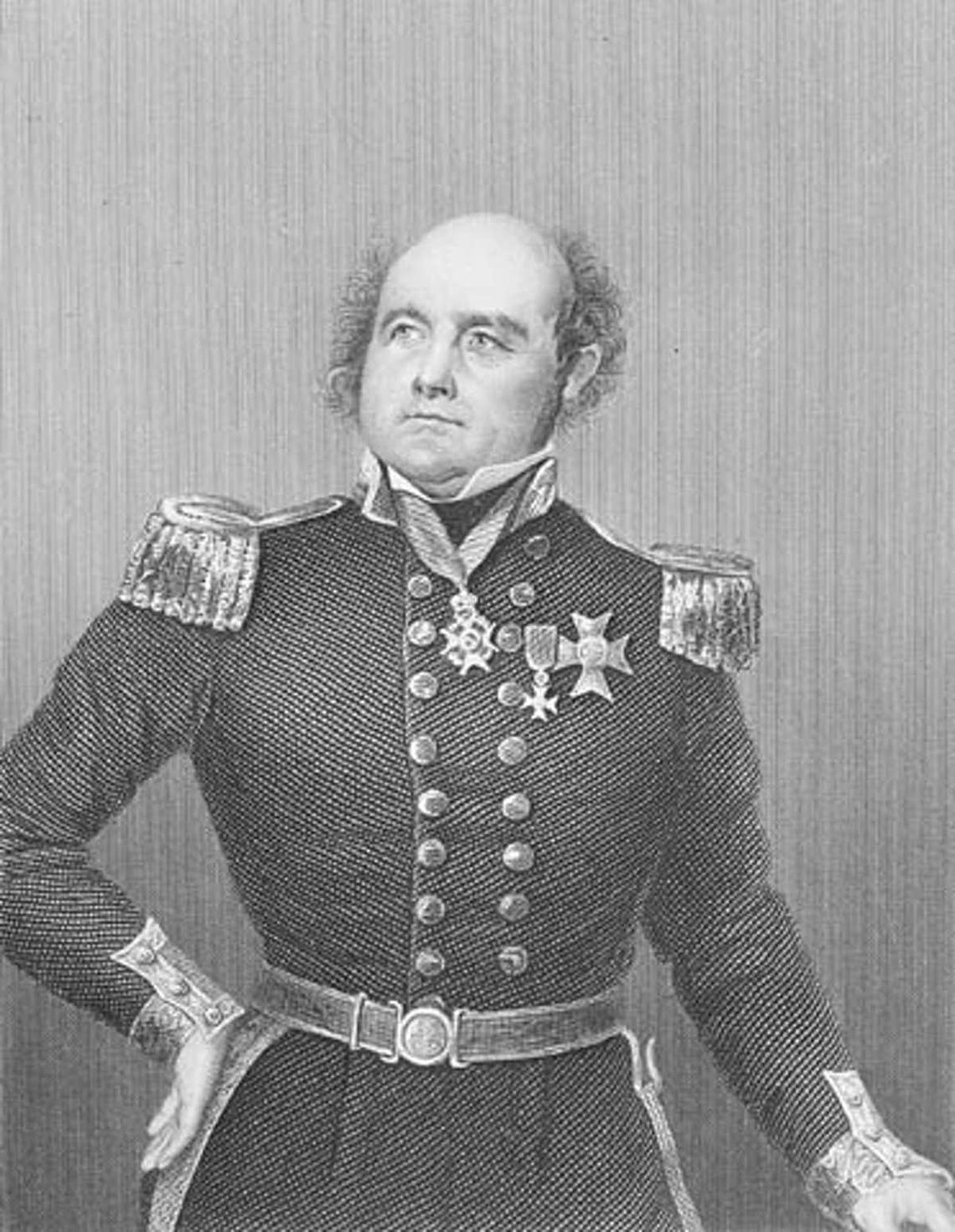

John Franklin (1786 – 1847)

Wikimedia Commons

While Franklin’s ships vanished without a trace, they were kept alive in the Inuit folklore. Accurate reporting of historic events, such as encounters with various exploration vessels, is a well-established characteristic of the Inuit oral tradition and tales of the lost ships have survived until the present day.

The first Inuit account was recorded by Irish explorer Sir Francis Leopold McClintock in The Voyage of the Fox in the Arctic Seas in 1859. McClintock, who joined a number of Royal Navy searches for the ships netween 1848 and 1859, was told that one of Franklin’s ships had been driven ashore by the ice in the marine area known as Ootgoolik, between Reilly Island and the Royal Geographical Society Islands. This information was supplied by Inuit near Cape Victoria, much further north.

In Unravelling the Franklin Mystery, historian David Woodman reports what the American Arctic explorer, Charles Francis Hall, heard about a ship in the same area from an Inuk whose name he rendered as Nuk-kee-che-uk in the 1860s. Nuk-kee-che-uk described the ship as beset in first-year ice, with four boats hanging in davits along its sides and one at the stern. A gangplank led from the deck down to the ice and the deck was housed over with canvas. The Inuit felt that a party of men had wintered on board the ship, and later tracks, not thought to be those of Inuits, were found on shore.

Nuk-kee-che-uk and others went aboard and found the corpse of a large man – fully-clothed and smelling badly. They ransacked the ship for items they could use. Returning after some time, they found that the ship had sunk, although the masts were still sticking out of the water. Subsequently large amounts of lumber and wreckage drifted ashore.

According to Woodman, a similar story was recounted by Inuit to another explorer, Lt. Frederick Schwatka during his expedition of 1878-80.

As the ships were first abandoned by both crews in the summer of 1848, one of them could have only reached this location if some members had returned to the ships, and managed to sail it south. But remarkably consistent versions of this account are still current in the nearby Inuit communities, which have helped explain the ship’s location.

In Encounters on the Passage, Dorothy Eber reports a story, handed down for decades, shared with her by Inuit elder Frank Analok, sometime between 1994 and 2008 in Cambridge Bay, Victoria Island. Analok believed that a ship had wintered off the south coast of Imnguyaaluk, the most northerly large island of the Royal Geographical Society group, with some of the crew camping on shore. The ship departed the following summer, and could be the one which has ended up off Hat Island.

Making a find

Parks Canada’s scientists have been attempting to find the ships each summer since 2008. Until now, their attempts have been unsuccessful. This summer, however, they have been helped by a number of other bodies including the Canadian Hydrographic Survey the Canadian Coast Guard, the Canadian Navy, the Royal Canadian Geographic Society, the Arctic Research Foundation, and the tourist operator Ocean Adventure. Their involvement enabled a more ambitious search to take place.

Sonar image of found ship.

Parks Canada/EPA

The proposed search area was north-west of King William Island, in the general direction of where the ships were abandoned. But the heavy ice conditions forced the expedition to concentrate its search much further south, in the southeast corner of Queen Maud Gulf. Four vessels were at their disposal, including the Coast Guard’s icebreaker Sir Wilfrid Laurier (Captain Bill Noon) and the Navy’s HMCS Kingston.

An additional purpose of the expedition was to map out these minimally-charted waters and on September 1, Scott Youngblood of the Canadian Hydrographic Survey took off by helicopter from the icebreaker to do so. He was heading for Hat Island, lying between O’Reilly Island and the Royal Geographical Society Islands, and was joined by two archaeologists: Douglas Stenton, director of Nunavut Culture and Heritage, and Richard Park of the University of Waterloo, Ontario. They, along with the helicopter pilot, strolled around on the tundra, keeping their eyes open for possible historical artifacts.

It was the helicopter pilot who made the first find: a fork-shaped metal object, about 43cm long, later identified as part of a ship’s davit. Then the archaeologists found a wooden hawse-plug; both items bore the Royal Navy’s “broad-arrow” symbol. Both artifacts were flown to Ottawa.

In view of these finds, the icebreaker Sir Wilfrid Laurier focused its search on the waters off the island. The diving boat Investigator was lowered and started towing a side-scan sonar “towfish” in a grid pattern. A very clear image of a large wooden ship sitting upright on the sea-bed in a depth of only 11 metres emerged very soon. This depth helps to confirm the veracity of the Inuit account of the ship’s masts sticking out of the water. The vessel appeared to be almost intact, although the masts were missing. Then an ROV (remotely operated underwater vehicle) was lowered and was soon relaying remarkably clear images of the ship, including details of deck planking and some cannon.

The discovery was the result of two fortunate coincidences: the heavy ice conditions further north which obliged the expedition to focus its attention further south, and the accident of the archeologists’ finding the two artefacts on the nearby island, which helped to focus the underwater search.

At 370 and 340 tons respectively, Erebus and Terror were almost identical vessels, and it is impossible to say which of them has been found at this point. But on September 11, Marc-André Bernier and Ryan Harris of Parks Canada’s underwater archaeology team flew back north, hoping to dive on the wreck during the limited window of opportunity before freeze-up. So, more artifacts will undoubtedly emerge soon and hopefully reveal the mystery of the ships’ disappearance.