Cardelia Fox, centre, and her sister Tamika with Dr. Greg Guilcher, an AHS oncologist.

June 8, 2016

Cardelia Fox, centre, and her sister Tamika with Dr. Greg Guilcher, an AHS oncologist.

The Alberta Children’s Hospital is believed to be the only pediatric centre in the world that is successfully using a novel stem cell transplant procedure to cure children of sickle cell anemia.

To date, seven girls and two boys with the genetic blood disorder have been cured through a process that first destroys the existing blood system, then grows a new system from the transplanted stem cells of a family member who is an immune match.

The same procedure is sometimes used in cancer patients as a leukemia treatment. A similar strategy is offered to patients undergoing radiation therapy or intensive chemotherapy; these patients can receive their own banked stem cells.

“To our knowledge, no one else is offering this protocol in children with sickle cell anemia,” says Dr. Greg Guilcher, an Alberta Health Services pediatric oncologist who leads the sickle cell blood and marrow transplant program at Alberta Children’s Hospital.

'We think we’re ahead of the curve in offering this curative therapy'

“We’re getting phone calls and emails from around the world from interested parents and other doctors. We think we’re ahead of the curve in offering this curative therapy as a standard of care,” says Dr. Guilcher, who is also an assistant professor in the Departments of Oncology and Paediatrics at the University of Calgary’s Cumming School of Medicine and Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute AND Arnie Charbonneau Cancer Institute.

Sickle cell anemia is a chronic illness in which blood cells can change into a sickle shape and block blood vessels. It varies in severity from patient to patient, but every organ is potentially at risk. Strokes, lung disease, heart strain and damage to the spleen and bones can result.

Even with the most advanced care available, life expectancy is 55-60 years. Many people with sickle cell anemia frequently visit the emergency department.

Cardelia Fox's match with her sister and amazing recovery

Cardelia Fox, 19, was one of the first patients to undergo the stem cell transplant procedure at Alberta Children’s Hospital. She was then 17.

She had the first of three childhood strokes when she was just six months old. She’s been in and out of hospital for much of her life — and previously required monthly life-saving blood transfusions.

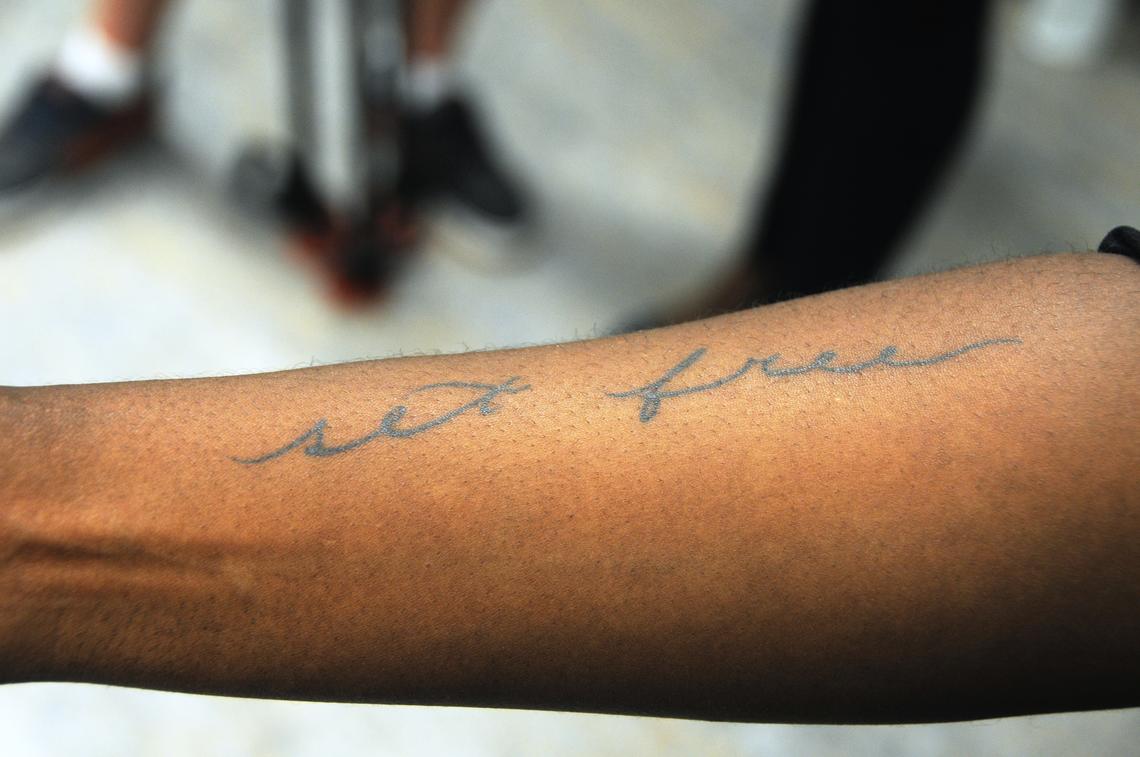

“Before the stem cell transplant I felt like I was trapped,” says Cardelia. “Without this treatment I would likely still be at Foothills getting blood transfusions every month.” On her 19th birthday, she had the words “set free” tattooed on the inside of her right forearm.

The tattoo Cardelia got after being cured.

Cardelia’s older sister, Tamika, proved to be a full match and provided the stem cells for transplant. The odds of a complete match (unaffected by sickle cell disease) being found within the family are only one in five. Without a family match, the transplant procedure is generally considered too risky to perform.

“When we learned I was a match there was never any question of whether or not I’d do it,” says Tamika Allen, now 22. “Of course I’m going to do this for my sister. It was such a good feeling to be able to help make her life better — now I call her my mini-me.”

'Now I call her my mini-me'

Cardelia now takes comfort knowing she no longer faces the same fate as her maternal grandmother, who died at age 35 from complications due to sickle cell anemia.

Genetically, one parent can pass on the mutation that causes sickle anemia without causing illness in their children, but if both parents pass it on, illness results. Sickle cell anemia mainly affects those of African descent, but is occasionally found in other populations.

In 2008, 16 children regularly attended the Sickle Cell Clinic at Alberta Children’s Hospital. Today, there are more than 80, an increase that can be attributed primarily to immigration, says Mike Leaker, head of the clinic, which welcomes patients from Alberta, Saskatchewan and eastern B.C.

“We now have some excellent medications that can change the course of the illness for many patients,” says Leaker. “But a drug is still a treatment, not a cure. For families the word ‘cure’ is incredibly powerful.”

Under the transplant protocol, patients are given medications to intensively suppress the immune system in the week leading up to the stem cell transplant. On the day before the infusion of the healthy donor stem cells, they also undergo a low-dose total body irradiation, in final preparation.

Growth expected in cell transplant procedure

Guilcher says he expects to see steady growth in interest in the stem cell transplant procedure, which was first performed in Calgary in 2009.

A team at Tom Baker Cancer Centre recently developed an innovative protective shield for boys undergoing total body irradiation, greatly reducing the chance they may become infertile. Infertility risks for girls are lower; successful pregnancies have been reported in the United States.

Significant advances in stem cell and bone marrow transplantation at the Alberta Children’s Hospital have been supported by generous community donations through the Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation.