April 6, 2020

“Baby blues” shouldn’t be brushed away

We’ve known for some time that a mother’s mental health plays a critical role in the development of her child. New mothers are routinely screened for post-partum depression as part of their follow-up care when they have a child.

A new study by a team of University of Calgary researchers suggests screening for depressive symptoms during the entire pregnancy may be valuable not only for mom, but for the developing child.

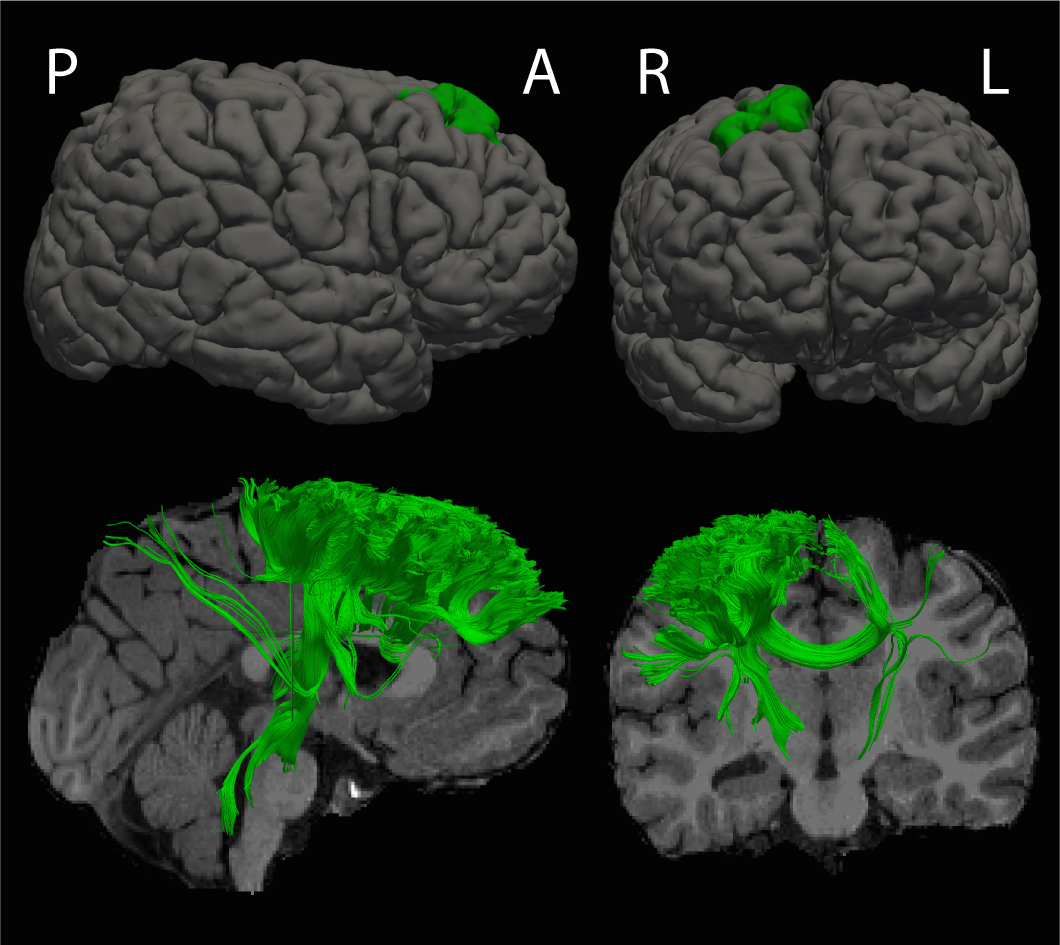

“We found relationships between brain structure in children and their mom’s depressive symptoms during the second trimester, and post-partum. Children whose mothers were more depressed had a thinner cortex (grey matter) and altered white matter,” said Catherine Lebel, PhD, an assistant professor in radiology at the Cumming School of Medicine, and member of the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute (ACHRI).

As a child grows, their brain grows, adapts and is flexible to input, which is what allows them to learn. As you get older your brain can still change, but not as easily. For example, learning a new language is easier when you’re five versus 45. Lebel’s study followed 52 women during their pregnancy. The women were screened for depressive symptoms during each trimester and three months after their child was born using a common mental health assessment tool, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Their children then underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of their brains between the ages of two and five years.

“What makes this study so important is that it starts to deliver on the promise of brain imaging to help in the early identification of children at greater risk for mental illness. We have known in general that the environment can shape brain development, but this is a landmark study providing the first evidence of how prenatal and postpartum depression can influence early brain development,” said Frank MacMaster, associate professor in the departments of psychiatry and paediatrics at the Cumming School of Medicine. MacMaster is also a member of the Hotchkiss Brain Institute and ACHRI.

The results, which have been published in Biological Psychiatry, showed kids whose mothers had higher depressive symptoms had the most mature brains. “These are all healthy, normal kids, and their moms underwent typical pregnancies,” said Lebel. “There is a lot of data showing that early adversity forces kids to mature early, which can be problematic as it may mean less flexibility and adaptability, and more difficulty learning.”

Depressive symptoms during and after pregnancy are not uncommon. They are often referred to as “baby blues”, but Lebel says depressive thoughts should always be taken seriously, and pregnant women should be encouraged to seek support and not be afraid to talk about how they’re feeling. According to the Canadian Mental Health Association, up to 20 per cent of new mothers experience postpartum depression.

While Lebel’s study focused on the structure of the brain, she hopes to continue her research to look at behavioral and cognitive function to see whether there are any links.

The brain imaging research program and scientists are funded by community donations through the Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation, and grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Canada Foundation for Innovation, and Alberta Economic Development and Trade.

The women who participated in this research are part of The Alberta Pregnancy Outcomes and Nutrition cohort.