July 17, 2020

Austrian artificial intelligence platform deciphers handwriting for researchers and historians

Hollywood and science fiction writers would have us believe that we should fear artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning.

You don’t have to go far to see robots, cyborgs and computers behaving badly. Take, for example, Terminator; 2001: A Space Odyssey; Ex Machina; WarGames; The Matrix; I, Robot; Westworld . . . (It’s a long list).

But in the world of cultural heritage, rather than raining down death and destruction, artificial intelligence and machine learning are of great benefit. Both are contributing to a greater understanding of our history by automating the transcription of handwritten documents.

Handwritten documents are often a preferred source when it comes to telling stories about history.

But they’re challenging to access. Handwriting is often difficult to read, and transcribing it by hand is usually tedious and time consuming. Sometimes, it’s just plain maddening.

Imagine, though, having the ability to automatically transcribe a diary or large collection of letters and at the end, get a searchable and printable transcript, all without typing a word. It would open a world of resources for students, researchers, historians and writers.

That’s the promise of artificial intelligence and machine learning in the form of handwriting text recognition (HTR).

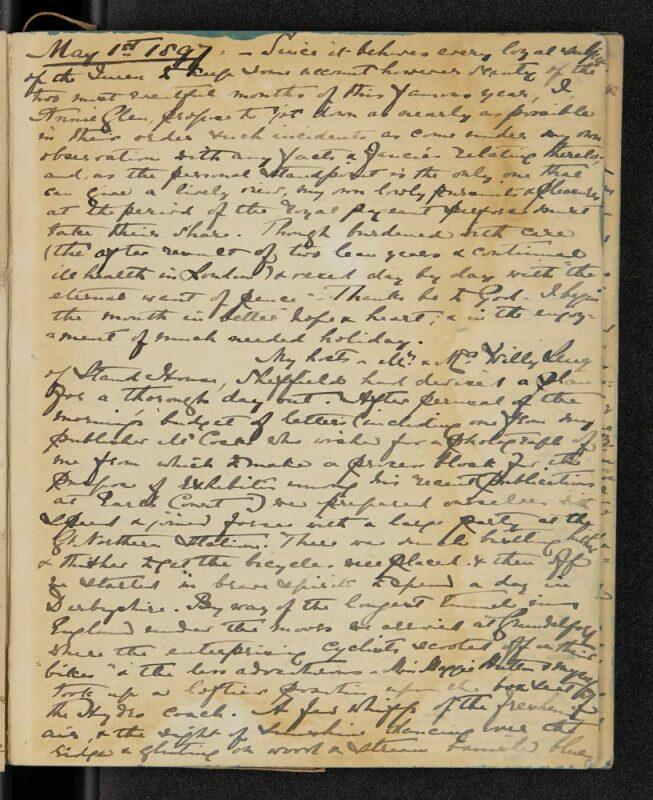

A page from Annie Glen Broder’s 1897 diary

Handwriting text recognition

Unlike optical character recognition (OCR), which has been in use for many years now, HTR is a recent innovation. It only dates back to the 1990s, and as a work in progress, it’s not yet fully automated nor flawless.

And at the moment, where OCR produces a searchable transcript automatically, HTR has to be trained to recognize an individual’s handwriting. It’s much like having to teach the first versions of speech-to-text software.

But with training comes automation. And this is where the power of artificial intelligence machine learning comes into play. Rather than activating the killer bots, Transkribus, an online HTR platform, is using artificial intelligence and machine learning to develop its transcription engine.

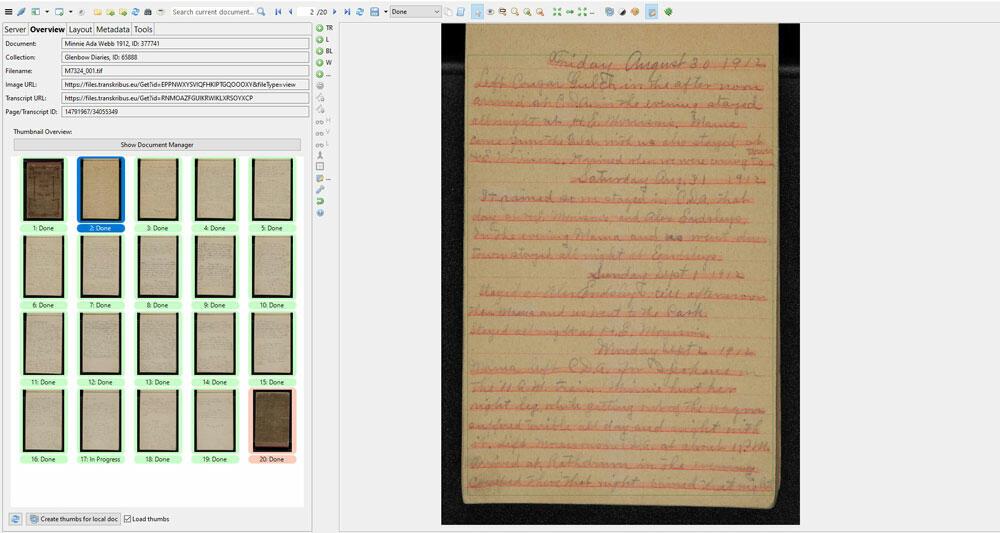

A page from Annie Glen Broder’s 1897 diary uploaded to Transkribus

Transkribus

Transkribus was developed in 2015 at the University of Innsbruck, Austria. It now has over 30,000 users worldwide, transcribing roughly 3,000 pages of handwritten text from historical documents every day.

Transkribus processes that data at the Computational Intelligence Technology Lab (CITL) at the University of Rostock to improve its algorithms. The eventual goal is to recognize handwriting automatically, without training.

In the meantime, however, users first have to create a model to teach Transkribus to recognize an individual’s writing.

To build a model, users have to upload the digital images into Trankribus and then transcribe about 75 pages of handwritten text (roughly 15,000 words). That’s enough data for Transkribus to begin recognizing an individual’s handwriting.

But there’s a catch: At this point, it’s really only helpful for large bodies of work written by a single author. Automated transcribing won’t work on a small group of letters or a short diary: It’s just not enough data.

Ancient text

With enough material, however, the automated transcription will work on modern or ancient materials written in Arabic, English, Old German, Polish, Bangla, Hebrew and Dutch.

The University of Innsbruck, for example, is training Transkribus to transcribe a text written in Middle High German known as the Ambraser Heldenbuch (Ambras Books of Heroes). Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, also the German king, commissioned a man named Han Ried to write this text in the early 16th century. Ried also wrote four other documents. So, in all, the five documents amount to roughly 500,000 words—that’s an ideal scenario for automated transcribing.

After analyzing the digital images of Minnie Ada Webb’s 1912 diary, Transkribus highlights the handwritten text to aid a transcriber.

Crowdsourcing

Automated HTR is an incredibly powerful tool in the right circumstances. If that power can’t be harnessed, however, Transkribus can still lighten the load during transcription projects as it is well suited for crowdsourced projects.

Once digital images of a diary or other text are uploaded to Transkribus, it analyzes the layout, highlighting handwritten text and linking it to each specific image. This feature allows multiple transcribers to claim pages.

It also ensures that there’s no overlap and that transcribed text remains with its source images.

Transkribus at UCalgary

Currently, staff with UCalgary’s library and archives (all of whom are working from home) are using Transkribus to transcribe 25 handwritten registers and seven diaries.

Three Alberta women wrote the diaries between the 1890s and the 1910s.

The registers, meanwhile, contain a total of 2,749 pages logging the material donations made to the Glenbow Library and Archives (between the 1950s and the 1980s.

UCalgary archivists are using the logs to help them make sense of the vast quantity of books and archival material in the Glenbow’s collections as it moves to UCalgary.

And being able to quickly search transcripts rather than the handwritten registers makes that job more straightforward.

But the registers contain private information, such as donor names and addresses. As a result, UCalgary can’t automate the transcription given that the University of Rostock processes the data.

Many different people also filled out the registers, which makes it difficult for an HTR model to run with any accuracy.

Even so, by merely using Transkribus as a transcribing platform, LCR staff have completed 859 of those pages since they began working at home in March.

Using Transkribus to transcribe a page from Minnie Ada Webb’s 1912 diary

Digitization

To work, HTR needs two things: handwritten documents and high-quality digital images of those documents.

It emphasizes the need for a robust and efficient digitization process. At UCalgary, digitization occurs in Digitization and Repository Services, which is located in the Taylor Family Digital Library, home to the Glenbow Western Research Centre.

HTR also provides an incentive to digitize more handwritten documents. Normally, diaries are not great candidates for digitization. Photographing and hand transcribing every page of a diary is slow and costly.

But as HTR improves, handwritten documents from the Glenbow Library and Archives and other UCalgary collections are more likely to be digitized and made available to students and researchers.

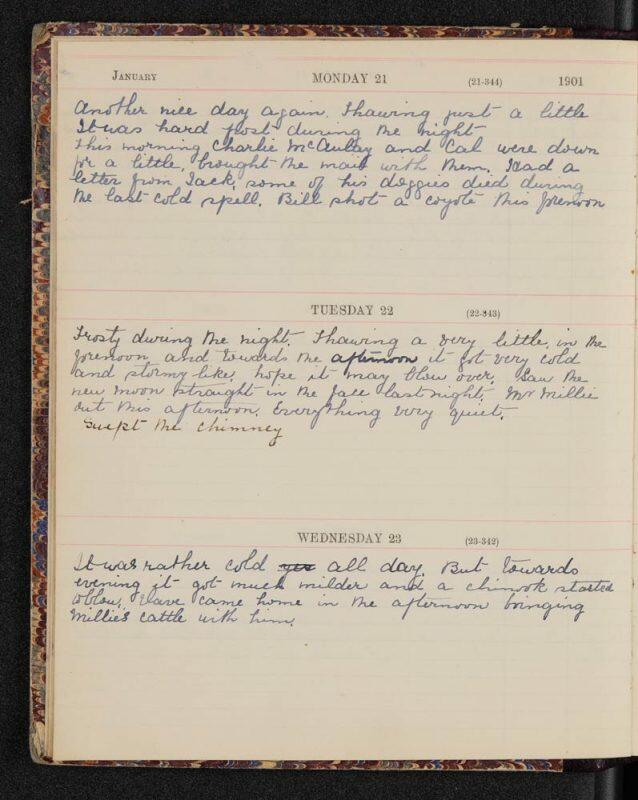

A page from Eliza Jane Wilson’s 1901 diary.

Outreach

Along with the promise of making more handwritten texts readily available, Transkribus is also opening doors here on campus.

LCR has also created a working group to expand the use of Transkribus and to make better use of it.

The group is small at the moment, comprised of LCR and Dr. Karen Bourrier, an associate professor in the Dept. of English. Even so, it has potential. As different groups come at it from different perspectives, each explores different functionalities in the software.

It’s a useful way to share tips and tricks, troubleshoot, share resources and inspire other projects.

While LCR is currently using Transkribus as a transcription platform, Dr. Bourrier is training the HTR to read the handwriting in more than 1,000 letters written by bestselling Victorian novelist Dinah Craik.

And when it comes to trying to deduce if a “c” is actually an “e” or maybe even an “a,” having knowledgeable transcribers to turn to can save a day’s work. In the world of transcribing handwriting, one letter or one word can derail someone’s entire day.

So, rather than fearing artificial intelligence and machine learning, HTR and Transkribus are showing a different side. As it relates to cultural heritage, there’s great potential. To begin with, it can save time. More importantly, however, it can help make historical handwritten text readily accessible.

And that gives us a better understanding of our history and our world—all without death and destruction.